Zero waste in the seafood industry

Can we turn 30 million metric tons of waste into an opportunity?

By Thor Sigfusson, Alexandra Leeper and Clara Jégousse.

The seafood industry has adapted to a great number of sustainable practices: from ethical fishing to novel technologies for processing, all in the spirit of cooperation toward zero waste. This article discusses different “waste” streams within the seafood industry, highlighting the efforts not only by the industry but also many efforts and pioneering work done by innovators and startups targeting waste reduction.

A thorough analysis of waste across the seafood industry remains elusive. Data for much of the current waste has simply not been collected. Contributing to this challenge is the complexity of this industry, spanning from small-scale fishing and aquaculture in rural, developing regions to vast trawling operations and high-tech, unmanned processing facilities. Here, we estimate 30 million metric tons of combined biological and non-biological waste is produced every year by the seafood industry based on available data, but many more waste streams (textiles, machinery, safety gears, etc.) have not been accounted for in this value and we emphasize the importance of further data collection to achieve true zero-waste in the global seafood sector.

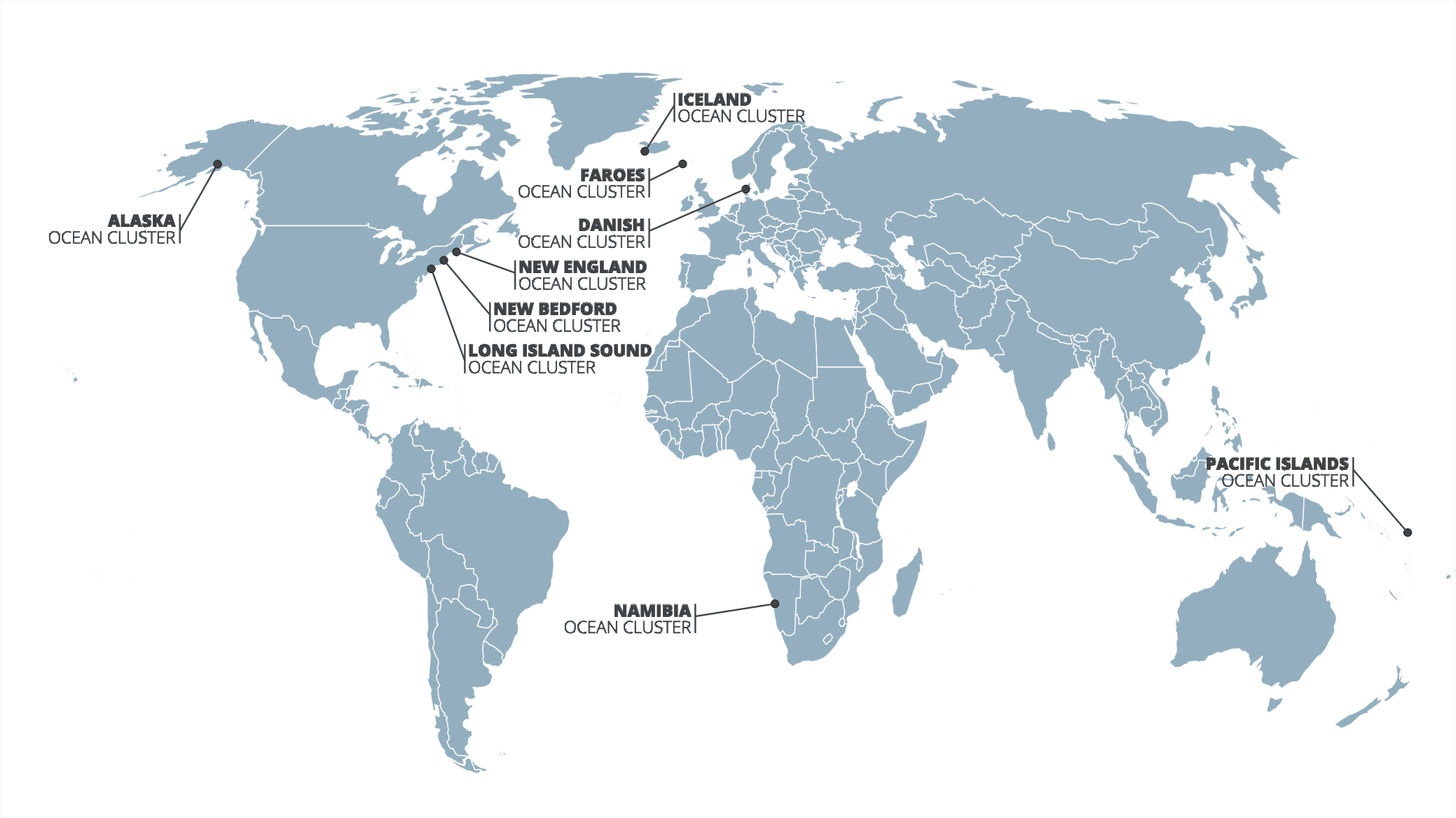

The Iceland Ocean Cluster has been a leader in advocating for zero waste in seafood side streams. Yet the issue of other waste streams in the industry persists. This analysis sheds light on existing data about various waste streams, supplemented by our research, which includes information gathered from large seafood corporations on their waste and waste reduction strategies.

Industrial waste is defined as the surplus materials or resources generated during the production or manufacturing processes of an industry, and which are not used in the primary product. This includes discarded materials, overproduction failing to meet quality standards, and any outputs not part of the final product. Reducing and managing this waste is crucial for sustainability, aiming to lessen environmental impact and maximize resource efficiency.

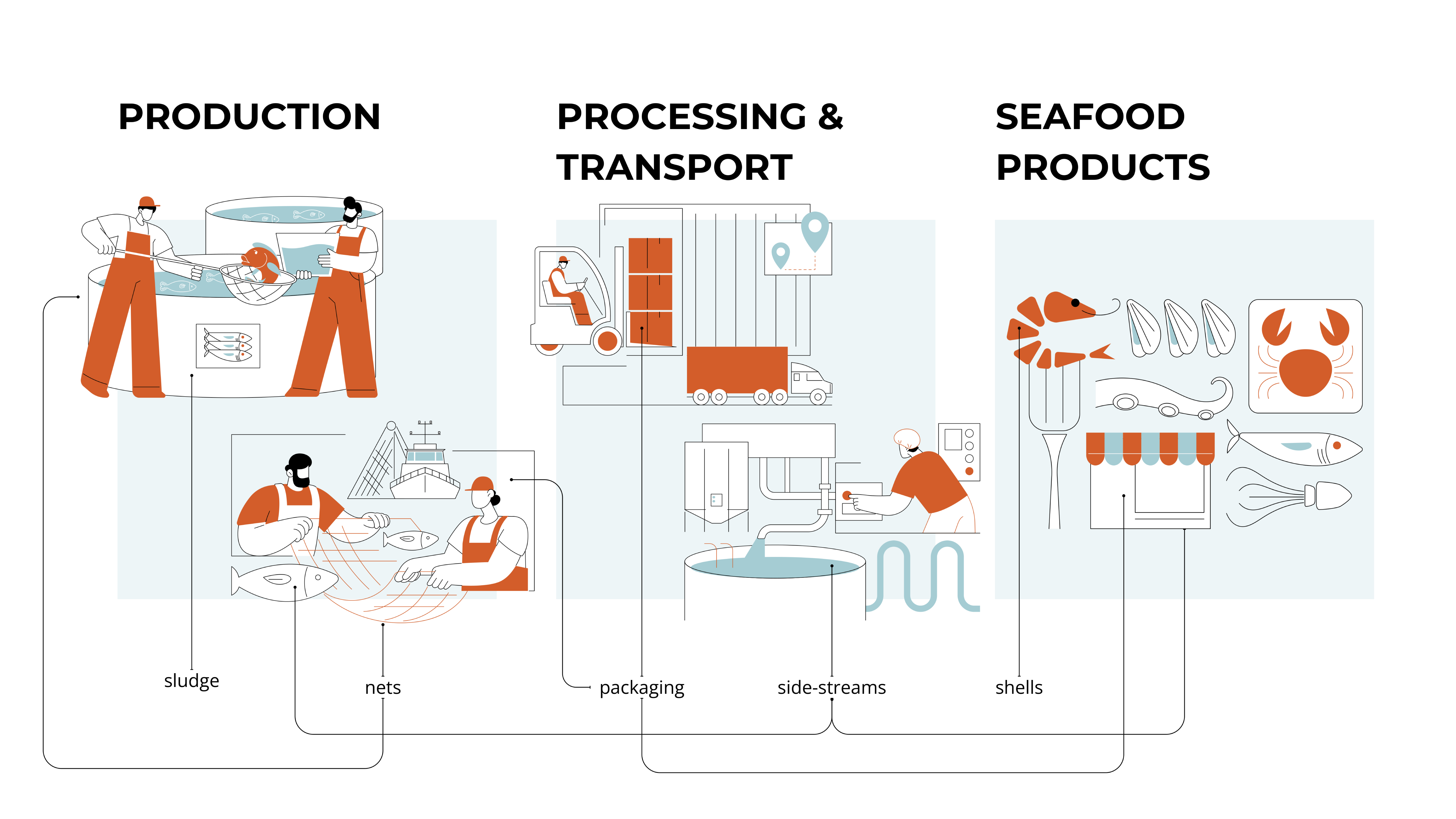

The products identified here as waste in the seafood industry are 1. Seafood side streams, 2. Shell waste, 3. Packaging and tubs, 4. Sludge, and 5. Nets.

1. Seafood side-streams

Seafood side-stream waste or byproduct waste consists of cut-offs from processing, heads, frames, guts, skin, and scales – which are often thrown back into the ocean where they disrupt marine food webs or they are thrown to landfill, where this organic material breaks down releasing methane- a potent Greenhouse Gas. Extracting valuable components like omega-3-rich oils, collagen, and enzymes from these side streams not only minimizes environmental impact but also creates additional revenue streams.

As the global aquaculture sector grows, this too creates processing side streams that add to this wasted volume and cumulatively contribute to the global carbon footprint associated with food waste.

In fisheries and aquaculture, it is estimated that 30-35 percent of the global fisheries and aquaculture production is either lost or wasted each year. Given the total production of seafood in the world, which is close to 200 million tonnes, the waste is close to 60-70 million tonnes (by-product waste in processing, discards of unwanted species on board of boats, storage- and transportation problems, etc.). Of these number, the Iceland Ocean Cluster has estimated that the waste in by-products in the fisheries industry (not including bycatch) is around 10 million tonnes. This is most likely a very conservative estimate.

The Iceland Ocean Cluster has mapped over 100 startups and small companies that are developing various products from whitefish and salmon. Most of these companies are Iceland and Norwegian based but there are also companies in other European countries, North- and South America on this list. The pioneers in this field range back over 80 years, like Lýsi Ltd. A company in Iceland, one of the largest producers of omega fish oil from whitefish. But in the last ten years, multiple startups have been established with various products in the field of beauty and health, nutraceuticals (supplements), medicine, leather, omega 3, and enzymes to name a few. Great examples include Kerecis, Nordlaks, Zymetech (acquired by Enzymatica in 2016), Nordic Fish Leather, Feel Iceland, Marine Collagen, and Ballstad to name just few. Companies such as Nordlaks in Norway are one of the pioneers in omega oil from salmon. The culinary field has also been actively observing ways to utilize all parts of the fish to serve demanding customers. Slippurinn, an Icelandic restaurant, led by chef Gísli Matthías Auðunsson, has probably been in the forefront here with the whitefish. In the Great Lakes region in North America, culinary competitions have been held with the aim to create value from fish side streams.

2.Shell waste

A considerable amount of waste generated in the seafood industry arises from shellfish, specifically crustaceans (like crabs, shrimp, and lobsters) and mollusks (such as clams, oysters, and mussels). According to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), there’s an estimated production of 25 million tonnes of shellfish in 2021. Given that the meat represents only 20 to 40% of the shellfish’s total weight, as opposed to 75% for fish, we can infer that shell waste could approach 10 million tonnes each year. This waste, often discarded into oceans or landfills, is detrimental to aquatic environments. Yet, these shells are rich in proteins, calcium carbonate, chitin, and chitosan, all of which hold significant potential for applications across various sectors.

Derived from crustaceans’ shells, chitin and chitosan have been used in a range of health and beauty products that have seen surging popularity. Companies such as Chitolytic, Mycodev, Genis, and Primex are key players in this industry. For instance, Primex’s offerings include pure chitosan ideal for food supplements and cosmetics, but they also developed their own beauty line under the brand ChitoCare as well as a natural water clarifier for pools called SeaKlear. Meanwhile, Genis, another Icelandic company, focuses on therapeutic chitin derivative development. Since its creation in 2005, Genis has been dedicated to pioneering research and innovation in chitin biology, Finally, culinary innovators globally are leveraging crab shell flavors in diverse gastronomic creations, including soups and infused oils.

Mollusks shells are also full of potential. In France, a country with a long tradition of cultivating oysters and mussels, the company Alegina transforms oyster shells into eco-friendly materials. Alegina is dedicated to creating sustainable materials and products using oyster shells, which they view as significant carbon sinks with a fully renewable supply each year. Their current material portfolio includes sea-sourced porcelain, draining pavements, and vegetated roofing systems, aiming to bring nature back into urban spaces. Another clever utilization is a paint containing oyster shell developed by Cool Roof. The paint reflects sunlight to reduce heat absorption by buildings and has shown promising results in lowering surface temperatures significantly during heatwaves, and potentially reducing indoor temperatures by 5 to 15°C, which makes it an excellent example of waste utilization.

3.Packaging and tubs

The variety of packaging in the seafood industry makes it very difficult to pinpoint the exact type and amount of waste from packaging. The type of material used in packaging has a great influence on its environmental impact. It is also difficult to determine the environmental impact of the packaging while considering the impact different packaging can have on shelf life of the product. Canned seafood represents a good example here. The canning material itself is environmentally negative but the canned product does save energy for conservation. The seafood industry is one of the largest consumers of expanded polystyrene for fish boxes.

According to EU data, approximately 200 kilograms of packaging waste is generated each year per capita[i]. Consumption of seafood products in the EU represents 6% of the total consumption for food products in the EU[ii]. Assuming the proportion of consumption represents the same amount of total packaging waste in the EU, gives around 4.2 million tonnes of packaging waste from seafood in the EU. We will not here estimate the global packaging waste in the seafood industry. More studies are needed to map different packaging and study complete supply chains regarding packaging.

Various new initiatives are being introduced in the seafood industry to tackle the huge amount of waste in packaging and fish tubs (containers). The company Sæplast in Iceland has introduced plastic fish tubs that are fully recyclable but most plastic fish tubs manufactured in the world are very difficult to recycle due the insulation or plastic material used. Tech companies such as Greenmax in the US and Runi in Denmark have introduced technology to fully recycle styrofoam boxes. Recycling companies, such as Regent Hill in the UK, are using used fish boxes from polystyrene to make material for building insulation.

4.Sludge

No comprehensive data is available on fish sludge in the global fish farming industry. A recent study estimated the amount of sludge generated from the Chilean aquaculture industry to be around 1.4 tons of fish sludge produced from every ton of farmed salmon[iii]. This would indicate that the salmon farming in the world produce sludge amounting to between 3-4 million tonnes a year.

Norwegian tech companies have been in the forefront of developing technology to handle sludge from land-based and closed fish farming facilities. Major innovators are Bioretur and Blue Ocean Technology offering technologies to dry sludge and produce organic material suitable for fertilizer and biogas.

5.Nets

Abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear in the seafood industry has recently been estimated by research published in Science Advances[iv]. The authors interviewed fishers around the world about how much fishing gear they lose annually and multiplied reported losses by global fishing effort data. Another study estimated that nearly 2% of all fishing gear is lost to the ocean annually. These included 740.000 kilometers of longline mainlines and 218 square kilometers of trawl nets. In addition, the authors estimated fishers losing 25 million pots and traps annually and 14 billion longline hooks[v]. The FAO estimated 640,000 tonnes of fishing are discarded in the oceans each year[vi]. These numbers do not include discarded fishing gear on land and no estimates have been made regarding the amount of fishing gear discarded in landfills. Given the lack of data, the total estimate of wasted fishing gear annually could be up to 1 million tonnes.

Over the last few years, many startup companies as well as non-profit programs and big international companies have recognized the value of recycling fishing nets. For instance, Net Your Problem, based in the United States, focuses on collecting and recycling old fishing nets, transforming them into new products Wake Lifeproof® phone case and Waterhaul® sunglasses. Across the ocean, in the United Kingdom, Journey Blue operates as a non-profit dedicated to creating consumer goods recycled fishing nets while the startup company Fishy Filaments recycles fishing nets and provides an ultra-low carbon supply of engineering grade Nylon 6. Over in France, Fil & Fab produces Nylo®, a material crafted entirely from recycled nets. In the Americas, Bureo is known for its initiatives in Chile and the USA, recycling discarded fishing nets into unique products such as skateboards and sunglasses. Hampidjan is an Icelandic company with an international reach, that have been implementing innovative net recycling and circular economic action.

On a larger scale, Interface[vii], a global manufacturer of carpet tiles, collaborates with the Zoological Society of London through the Net-Works program. This initiative supports coastal communities in developing countries by collecting discarded fishing nets, which are then recycled into yarn for creating carpet tiles. These examples underscore the global commitment to combating marine plastic pollution through innovative recycling practices.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted key waste channels within the global seafood sector and the numerous innovative efforts aimed at reducing these waste channels. The Iceland Ocean Cluster has underscored the value of innovation and grassroots initiatives in advancing the circular economy within the seafood industry. The potential of AI to address unwanted catch, better utilization of seafood, quality control and environmental issues is huge and further collaboration between the seafood industry, R&D and startups is crucial to utilize these opportunities. The many pioneers mentioned here are just examples of the innovation ongoing in the field of zero-waste. These initiatives often inspire industry to adopt new technologies or methods that are economically and environmentally beneficial. However, the journey ahead presents considerable obstacles, yet the enhanced cooperation among companies is making a positive impact. It is crucial for governments and investors worldwide to provide more support and investment in these initiatives, fostering further collaboration between industry and pioneers of zero-waste solutions. Here accelerators like Hatch Blue, Fish2.0 and similar initiatives worldwide extremely important.

Numerous seafood industry enterprises are adopting circular economy principles, focusing on creating self-sustaining systems that minimize waste and design products for recyclability or reuse, including packaging innovations. It is vital to encourage these firms to deepen their commitment to the zero-waste agenda. Nonetheless, there is a pressing need for additional data collection to quantify the challenges associated with the waste streams mentioned.

—

[i] Eurostat. “Packaging waste statistics.” Statistics Explained. European Commission. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Packaging_waste_statistics. Accessed March 26, 2024.

[ii] European Commission. “Facts and figures on consumption under the Common Fisheries Policy.” European Commission – Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. Available at: https://oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/facts-and-figures/facts-and-figures-common-fisheries-policy/consumption_en. Accessed March 26, 2024.

[iii] Celis, J., Sandoval, M., & Barra, R. (2008). Plant response to salmon wastes and sewage sludge used as organic fertilizer on two degraded soils under greenhouse conditions. Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research, 68(3), 274-283.

[iv] Richardson, K., et al. (2022). Global estimates of fishing gear lost to the ocean each year. Sci. Adv., 8, eabq0135. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq0135.

[v] Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). “Abandoned Fishing Gear.” CSIRO. Available at: https://www.csiro.au/en/news/all/articles/2022/october/abandoned-fishing-gear. Accessed March 25, 2024.

[vi] Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T., & Cappell, R. (2009). Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear. UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies No.185; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, No. 523. Rome: UNEP/FAO.

[vii] Interface. (2015, October 21). Net-Works: The world’s first inclusive business model to recycle discarded fishing nets. [Press release]

For further information or inquiries please contact the author, Thor Sigfusson at: Thor@sjavarklasinn.is